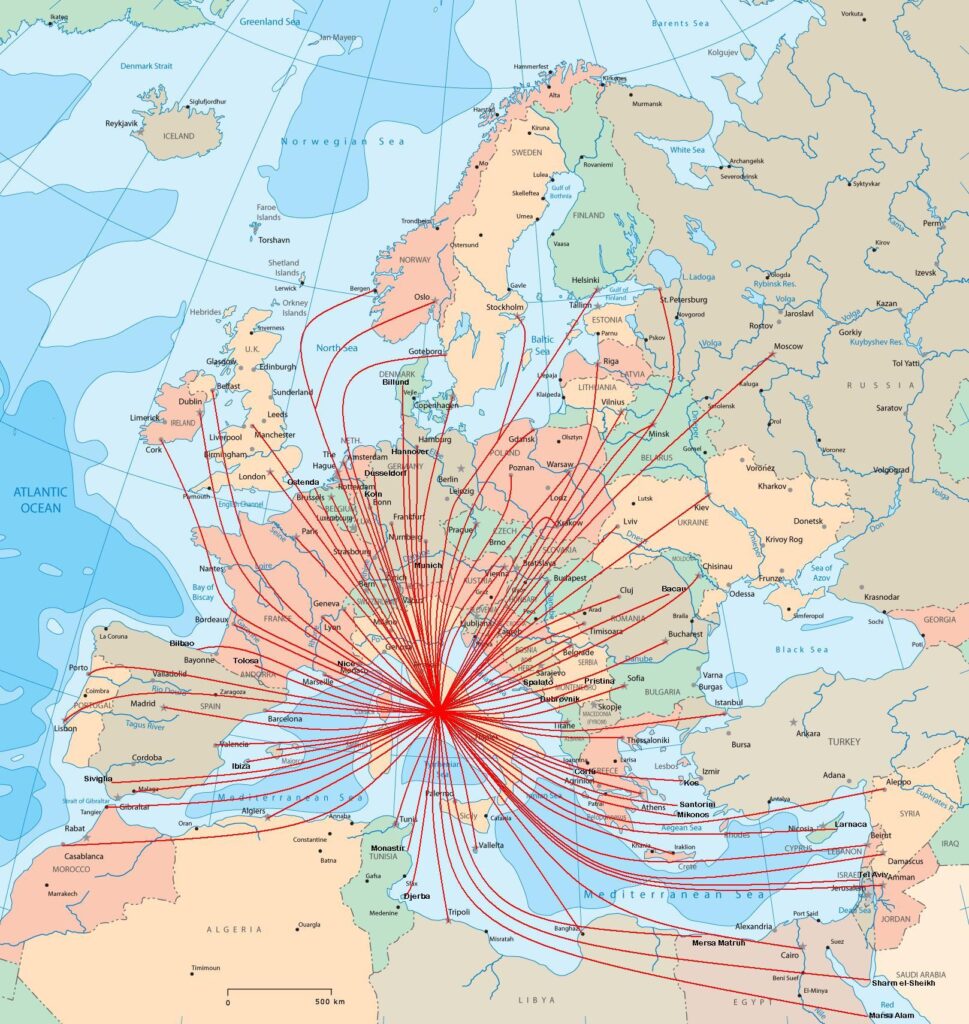

EUROPE- Every year, tens of millions of people travel across vast oceans by air. These days, it’s just usual. Major routes, like the one connecting London’s Heathrow Airport (LHR) with New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport (JFK), see more than a dozen nonstop daily flights in both directions.

Their vast airports accommodate numerous terminals linked by private rail networks, facilitating the movement of passengers and their belongings. Thousands of laborers begin their shifts early in the morning and don’t finish until the final aircraft safely takes off. Flyers are aware that about 76,000 individuals are employed at LHR.

Transatlantic Flight Routes

Regarding airlines deciding where to fly, one method used today is through a trade show called Routes. This event attracts thousands of airline and airport executives who come together to discuss potential new services. With travel and tourism making up about 10% of global employment, introducing new flights can significantly benefit local economies.

Governments and tourism boards sometimes provide financial support or promotional assistance for new flight routes. During Routes events, executives gather around tables with their laptops open, reviewing data to make informed decisions.

But how did the first European gateway for passenger flights from the U.S. come about?

The story is well documented at its place of origin, the Foynes Flying Boat & Maritime Museum in Foynes, Ireland. Situated on the Shannon Estuary, it’s just a 50-minute drive from Shannon Airport. It served as Ireland’s primary gateway for many years before nonstop flights from North America to Dublin were allowed. The decision to establish this stopover was initially political, aiming to encourage visitors to spend money in rural western areas. However, the original selection was entirely merit-based.

Lindbergh and Trippe’s Impact on Air Travel

In 1933, Charles Lindbergh influenced the decision to establish the initial version of Heathrow Airport. Renowned for his historic nonstop flight between North America and Continental Europe in 1927, Lindbergh later served as a consultant to the iconic Pan Am founder and CEO, Juan Trippe.

Trippe’s visionary leadership played a pivotal role in shaping the trajectory of the aviation industry. He spearheaded initiatives that propelled the jet age and subsequently the era of jumbo jets.

Trippe’s advocacy led McDonald Douglas’s development of the Douglas DC-8 jetliner and spurred Boeing to manufacture the 707. Moreover, he was pivotal in launching the Boeing 747, often called the “queen of the skies.”

Trippe’s forward-thinking approach extended to supporting supersonic travel and advocating for passenger flights to the moon. Additionally, his partnership with Dassault for its inaugural private jet order marked the entry of the French OEM into the business aviation sector.

Lindbergh and Trippe’s Route Surveys

In the collaboration between Trippe and Lindbergh, the latter played a crucial role in surveying potential new routes that Trippe aimed to establish. Trippe would convey his desired destinations to Lindbergh, who then pilot flights to those locations using the primitive propeller airplanes of that era.

During the 1920s and 30s, Lindbergh scouted for suitable landing spots for Pan Am’s flying boats, often contending with harsh coastal weather in remote areas to find sheltered locations with calm waters for safe seaplane landings.

During this time, the availability of concrete runways was limited, with their widespread construction largely occurring during World War II. This development laid the groundwork for the post-war surge in air travel and marked the end of the flying boat era.

By the 1930s, Lindbergh had charted routes to South America and Asia, prompting Trippe’s eagerness to initiate regular passenger flights between the U.S. and Europe. However, the endeavor was fraught with peril, particularly due to longer stretches of ocean with few safe landing options.

Challenges of Transatlantic Flying Boat

While many believed flying boats were safe, especially after the Hindenburg disaster, the reality in the North Atlantic was quite different: waves could easily destroy them upon impact. These aircraft also couldn’t fly high enough to avoid storms, necessitating navigation around them or turning back if avoidance wasn’t possible.

In contrast to today’s advanced cockpits, navigation relied on sextants and celestial observations to plot courses. Periodically, boats would descend close to the ocean surface to release a float with smoke, aiding in wind calculation for course correction.

In one instance, a flight departing Foynes had to return after 12 hours due to adverse conditions. One passenger, waking up during the return, mistook the dispatcher for someone from Ireland, jokingly commenting on their resemblance.

Winter weather often made a northern route impractical for large parts of the year, forcing flights to take a southern path via Lisbon or, if necessary, through Trinidad, Brazil, and West Africa before returning to Europe.

The Evolution and End of Transatlantic Flying Boats

It took numerous years and various iterations of flying boats to develop one with sufficient range for a safe trip from the U.S. to Europe via Foynes. However, due to the substantial fuel consumption required to lift these large airframes off the water, there were several unsuccessful attempts to refuel them mid-flight, deeming them unsafe for passenger service.

Shortly after successfully establishing transatlantic routes in 1939, the outbreak of World War II with Hitler’s invasion of Poland led Pan Am to cease commercial operations on the route. Despite the wartime challenges, flying boats continued operating, capitalizing on Ireland’s neutral stance.

They were crucial in transporting Allied diplomats and politicians, with Foynes as a terminus instead of routes extending to Bristol or Poole in England.

By the war’s conclusion, nonstop transatlantic flights became feasible with the advent of airplanes equipped to make the journey and the proliferation of runways worldwide. This marked the end of the flying boat era. However, during its brief prominence, the small Irish village of Foynes welcomed notable figures such as Winston Churchill, Eleanor Roosevelt, Ernest Hemingway, John F. Kennedy, Bob Hope, and Humphrey Bogart.

Legacy of Foynes flying boat and Irish Coffee

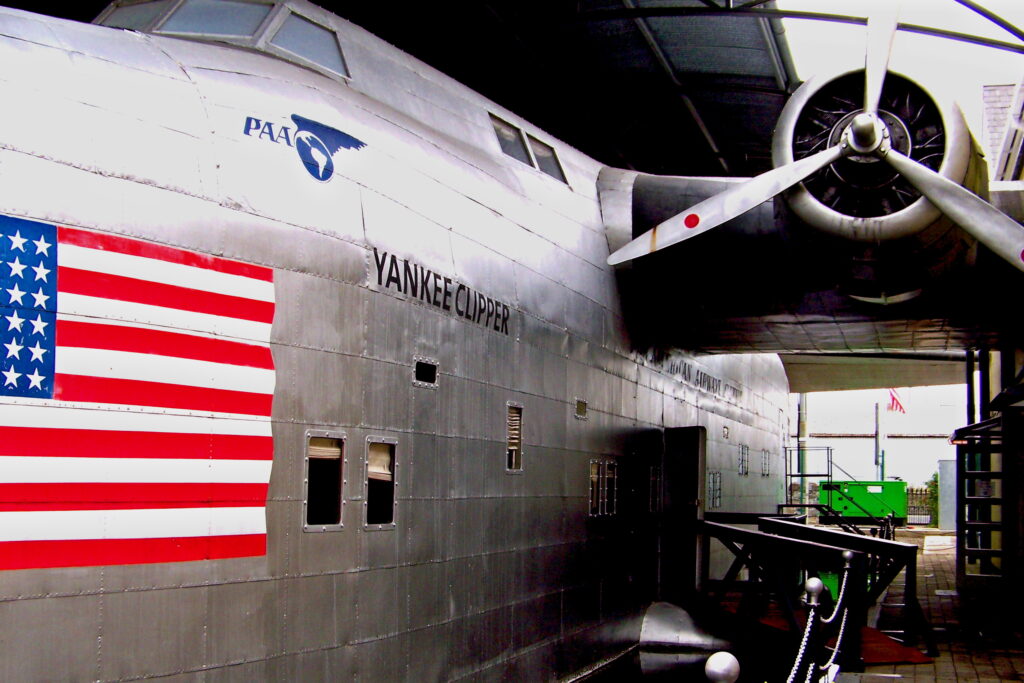

At the museum, there stands a life-size replica of the Yankee Clipper, a double-decker Boeing 314 flying boat. Visitors can stroll through and occupy the cockpit, experiencing considerably more legroom than modern flights. Since flights lasted most of the day, sleeping arrangements were available.

The museum houses numerous artifacts, ranging from dining ware used during meal services to the navigational instruments utilized by flight crews. Additionally, visitors can immerse themselves in abundant photos, video displays, and an intriguing 18-minute film featuring archived footage from news reports of that era.

While much of this history remains unfamiliar to many, the legacy of Foynes and the flying boats lives on, notably through the creation of Irish Coffee.

This renowned beverage originated from a local chef who concocted it one chilly night upon hearing that a Pan Am flying boat was returning to Foynes due to inclement weather. Welcoming the chilled passengers from the North Atlantic’s gusting winds on the Shannon Estuary, he prepared a special drink to warm them up.

This beverage comprised freshly brewed coffee infused with a generous dose of Irish whiskey sugar and topped with a dollop of fresh cream. Served in a glass with a handle and accompanied by a long, thin spoon—just as it is today.

Stay tuned with us. Further, follow us on social media for the latest updates.

Join us on Telegram Group for the Latest Aviation Updates. Subsequently, follow us on Google News.